Public discussions of discrimination in tech often result in someone claiming that discrimination is impossible because of market forces. Here's a quote from Marc Andreessen that sums up a common view.

Let's launch right into it. I think the critique that Silicon Valley companies are deliberately, systematically discriminatory is incorrect, and there are two reasons to believe that that's the case. ... No. 2, our companies are desperate for talent. Desperate. Our companies are dying for talent. They're like lying on the beach gasping because they can't get enough talented people in for these jobs. The motivation to go find talent wherever it is unbelievably high.

Marc Andreessen's point is that the market is too competitive for discrimination to exist. But VC funded startups aren't the first companies in the world to face a competitive hiring market. Consider the market for PhD economists from, say, 1958 to 1987. Alan Greenspan had this to say about how that market looked to his firm, Townsend-Greenspan.

Townsend-Greenspan was unusual for an economics firm in that the men worked for the women (we had about twenty-five employees in all). My hiring of women economists was not motivated by women's liberation. It just made great business sense. I valued men and women equally, and found that because other employers did not, good women economists were less expensive than men. Hiring women . . . gave Townsend-Greenspan higher-quality work for the same money . . .

Not only did competition not end discrimination, there was enough discrimination that the act of not discriminating provided a significant competitive advantage for Townsend-Greenspan. And this is in finance, which is known for being cutthroat. And not just any part of finance, but one where it's PhD economists hiring other PhD economists. This is one of the industries where the people doing the hiring are the most likely to be familiar with both the theoretical models and the empirical research showing that discrimination opens up market opportunities by suppressing wages of some groups. But even that wasn't enough to equalize wages between men and women when Greenspan took over Townsend-Greenspan in 1958 and it still wasn't enough when Greenspan left to become chairman of the Fed in 1987. That's the thing about discrimination. When it's part of a deep-seated belief, it's hard for people to tell that they're discriminating.

And yet, in discussions on tech hiring, people often claim that, since markets and hiring are perfectly competitive or efficient, companies must already be hiring the best people presented to them. A corollary of this is that anti-discrimination or diversity oriented policies necessarily mean "lowering the bar since these would mean diverging from existing optimal hiring practices. And conversely, even when "market forces" aren't involved in the discussion, claiming that increasing hiring diversity necessarily means "lowering the bar" relies on an assumption of a kind of optimality in hiring. I think that an examination of tech hiring practices makes it pretty clear that practices are far from optimal, but rather than address this claim based on practices (which has been done in the linked posts), I'd look to look at the meta-claim that market forces make discrimination impossible. People make vauge claims about market efficiency and economics, like this influential serial founder who concludes his remarks on hiring with "Capitalism is real and markets are efficient.". People seem to love handwave-y citations of "the market" or "economists".

But if we actually read what economists have to say on how hiring markets work, they do not, in general, claim that markets are perfectly efficient or that discrimination does not occur in markets that might colloquially be called highly competitive. Since we're talking about discrimination, a good place to start might be Becker's seminal work on discrimination. What Becker says is that markets impose a cost on discrimination, and that under certain market conditions, what Becker calls "taste-based" discrimination occuring on average doesn't mean there's discrimination at the margin. This is quite a specific statement and, if you read other papers in the literature on discrimination, they also make similarly specific statements. What you don't see is anything like the handwave-y claims in tech discussions, that "market forces" or "competition" is incompatible with discrimination or non-optimal hiring. Quite frankly, I've never had a discussion with someone who says things like "Capitalism is real and markets are efficient" where it appears that they have even a passing familiarity with Becker's seminal work in the field of the economics of discrimination or, for that matter, any other major work on the topic.

In discussions among the broader tech community, I have never seen anyone make a case that the tech industry (or any industry) meets the conditions under which taste-based discrimination on average doesn't imply marginal taste-based discrimination. Nor have I ever seen people make the case that we only have taste-based discrimination or that we also meet the conditions for not having other forms of discrimination. When people cite "efficient markets" with respect to hiring or other parts of tech, it's generally vague handwaving that sounds like an appeal to authority, but the authority is what someone might call a teenage libertarian's idea of how markets might behave.

Since people often don't find abstract reasoning of the kind you see in Becker's work convincing, let's look at a few concrete examples. You can see discrimination in a lot of fields. A problem is that it's hard to separate out the effect of discrimination from confounding variables because it's hard to get good data on employee performance v. compensation over time. Luckily, there's one set of fields where that data is available: sports. And before we go into the examples, it's worth noting that we should, directionally, expect much less discrimination in sports than in tech. Not only is there much better data available on employee performance, it's easier to predict future employee performance from past performance, the impact of employee performance on "company" performance is greater and easier quantify, and the market is more competitive. Relatively to tech, these forces both increase the cost of discrimination while making the cost more visible.

In baseball, Gwartney and Haworth (1974) found that teams that discriminated less against non-white players in the decade following de-segregation performed better. Studies of later decades using “classical” productivity metrics mostly found that salaries equalize. However, Swartz (2014), using newer and more accurate metrics for productivity, found that Latino players are significantly underpaid for their productivity level. Compensation isn't the only way to discriminate -- Jibou (1988) found that black players had higher exit rates from baseball after controlling for age and performance. This should sound familiar to anyone who's wondered about exit rates in tech fields.

This slow effect of the market isn't limited to baseball; it actually seems to be worse in other sports. A review article by Kahn (1991) notes that in basketball, the most recent studies (up to the date of the review) found an 11%-25% salary penalty for black players as well as a higher exit rate. Kahn also noted multiple studies showing discrimination against French-Canadians in hockey, which is believed to be due to stereotypes about how French-Canadian men are less masculine than other men.

In tech, some people are concerned that increasing diversity will "lower the bar", but in sports, which has a more competitive hiring market than tech, we saw the opposite, increasing diversity raised the level instead of lowering it because it means hiring people on their qualifications instead of on what they look like. I don't disagree with people who say that it would be absurd for tech companies to leave money on the table by not hiring qualified minorities. But this is exactly what we saw in the sports we looked at, where that's even more absurd due to the relative ease of quantifying performance. And yet, for decades, teams left huge amounts of money on the table by favoring white players (and, in the case of hockey, non-French Canadian players) who were, quite simply, less qualified than their peers. The world is an absurd place.

In fields where there's enough data to see if there might be discrimination, we often find discrimination. Even in fields that are among the most competitive fields in existence, like major professional sports. Studies on discrimination aren't limited to empirical studies and data mining. There have been experiments showing discrimination at every level, from initial resume screening to phone screening to job offers to salary negotiation to workplace promotions. And those studies are mostly in fields where there's something resembling gender parity. In fields where discrimination is weak enough that there's gender parity or racial parity in entrance rates, we can see steadily decreasing levels of discrimination over the last two generations. Discrimination hasn't been eliminated, but it's much reduced.

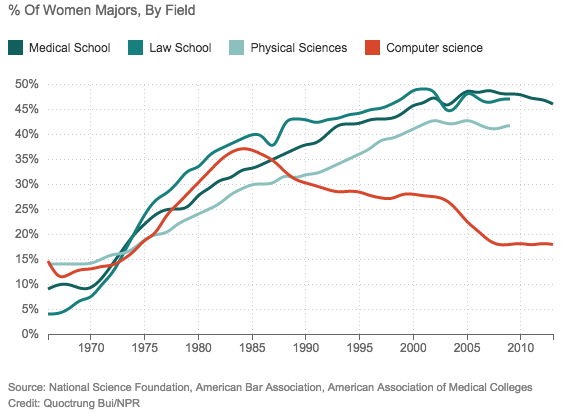

And then we have computer science. The disparity in entrance rates is about what it was for medicine, law, and the physical sciences in the 70s. As it happens, the excuses for the gender disparity are the exact same excuses that were trotted out in the 70s to justify why women didn't want to go into or couldn't handle technical fields like medicine, economics, finance, and biology.

One argument that's commonly made is that women are inherently less interested in the "harder" sciences, so you'd expect more women to go into biology or medicine than programming. There are two major reasons I don't find that line of reasoning to be convincing. First, proportionally more women go into fields like math and chemical engineering than go into programming. I think it's pointless to rank math and the sciences by how "hard science" they are, but if you ask people to rank these things, most people will put math above programming and if they know what's involved in a chemical engineering degree, I think they'll also put chemical engineering above programming and yet those fields have proportionally more women than programming. Second, if you look at other countries, they have wildly different proportions of people who study computer science for reasons that seem to mostly be cultural. Given that we do see all of this variation, I don't see any reason to think that the U.S. reflects the "true" rate that women want to study programming and that countries where (proportionally) many more women want to study programming have rates that are distorted from the "true" rate by cultural biases.

Putting aside theoretical arguments, I wonder how it is that I've had such a different lived experience than Andreessen. His reasoning must sound reasonable in his head and stories of discrimination from women and minorities must not ring true. But to me, it's just the opposite.

Just the other day, I was talking to John (this and all other names were chosen randomly in order to maintain anonymity), a friend of mine who's a solid programmer. It took him two years to find a job, which is shocking in today's job market for someone my age, but sadly normal for someone like him, who's twice my age.

You might wonder if it's something about John besides his age, but when a Google coworker and I mock interviewed him he did fine. I did the standard interview training at Google and I interviewed for Google, and when I compare him to that bar, I'd say that his getting hired at Google would pretty much be a coin flip. Yes on a good day; no on a bad day. And when he interviewed at Google, he didn't get an offer, but he passed the phone screen and after the on-site they strongly suggested that he apply again in a year, which is a good sign. But most places wouldn't even talk to John.

And even at Google, which makes a lot of hay about removing bias from their processes, the processes often fail to do so. When I referred Mary to Google, she got rejected in the recruiter phone screen as not being technical enough and I saw William face increasing levels of ire from a manager because of a medical problem, which eventually caused him to quit.

Of course, in online discussions, people will call into question the technical competency of people like Mary. Well, Mary is one of the most impressive engineers I've ever met in any field. People mean different things when they say that, so let me provide a frame of reference: the other folks who fall into that category for me include an IBM Fellow, the person that IBM Fellow called the best engineer at IBM, a Math Olympiad medalist who's now a professor at CMU, a distinguished engineer at Sun, and a few other similar folks.

So anyway, Mary gets on the phone with a Google recruiter. The recruiter makes some comments about how Mary has a degree in math and not CS, and might not be technical enough, and questions Mary's programming experience: was it “algorithms” or “just coding”? It goes downhill from there.

Google has plenty of engineers without a CS degree, people with degrees in history, music, and the arts, and lots of engineers without any degree at all, not even a high school diploma. But somehow a math degree plus my internal referral mentioning that this was one of the best engineers I've ever seen resulted in the decision that Mary wasn't technical enough.

You might say that, like the example with John, this is some kind of a fluke. Maybe. But from what I've seen, if Mary were a man and not a woman, the odds of a fluke would have been lower.

This dynamic isn't just limited to hiring. I notice it every time I read the comments on one of Anna's blog posts. As often as not, someone will question Anna's technical chops. It's not even that they find a "well, actually" in the current post (although that sometimes happens); it's usually that they dig up some post from six months ago which, according to them, wasn't technical enough.

I'm no more technical than Anna, but I have literally never had that happen to me. I've seen it happen to men, but only those who are extremely high profile (among the top N most well-known tech bloggers, like Steve Yegge or Jeff Atwood), or who are pushing an agenda that's often condescended to (like dynamic languages). But it regularly happens to moderately well-known female bloggers like Anna.

Differential treatment of women and minorities isn't limited to hiring and blogging. I've lost track of the number of times a woman has offhandedly mentioned to me that some guy assumed she was a recruiter, a front-end dev, a wife, a girlfriend, or a UX consultant. It happens everywhere. At conferences. At parties full of devs. At work. Everywhere. Not only has that never happened to me, the opposite regularly happens to me -- if I'm hanging out with physics or math grad students, people assume I'm a fellow grad student.

When people bring up the market in discussions like these, they make it sound like it's a force of nature. It's not. It's just a word that describes the collective actions of people under some circumstances. Mary's situation didn't automatically get fixed because it's a free market. Mary's rejection by the recruiter got undone when I complained to my engineering director, who put me in touch with an HR director who patiently listened to the story and overturned the decision. The market is just humans. It's humans all the way down.

We can fix this, if we stop assuming the market will fix it for us.

Also, note that although this post was originally published in 2014, it was updated in 2020 with links to some more recent comments and a bit of re-organization.

Thanks to Leah Hanson, Kelley Eskridge, Lindsey Kuper, Nathan Kurz, Scott Feeney, Katerina Barone-Adesi, Yuri Vishnevsky, @teles_dev, "Negative12DollarBill", and Patrick Roberts for feedback on this post, and to Julia Evans for encouraging me to post this when I was on the fence about writing this up publicly.

Note that all names in this post are aliases, taken from a list common names in the U.S. as of 1880.