There's an ongoing debate over whether "AI" will ever be good enough to displace humans and, if so, when it will happen. In this debate, the optimists tend to focus on how much AI is improving and the pessimists point to all the ways AI isn't as good as an ideal human being. I think this misses two very important factors.

One, is that jobs that are on the potential chopping block, such as first-line customer service, customer service for industries that are either low margin or don't care about the customer, etc., tend to be filled by apathetic humans in a poorly designed system, and humans aren't even very good at simple tasks they care a lot about. When we're apathetic, we're absolutely terrible; it's not going to take a nearly-omniscient sci-fi level AI to perform at least somewhat comparably.

Two, companies are going to replace humans with AI in many roles even if AI is significantly worse as if the AI is much cheaper. One place this has already happened (though perhaps this software is too basic to be considered an AI) is with phone trees. Phone trees are absolutely terrible compared to the humans they replaced, but they're also orders of magnitude cheaper. Although there are high-margin high-touch companies that won't put you through a phone tree, at most companies, for a customer looking for customer service, a huge number of work hours have been replaced by phone trees, and were then replaced again by phone trees with poor AI voice recognition that I find worse than old school touch pad phone trees. It's not a great experience, and may get much worse when AI automates even more of the process.

But on the other hand, here's a not-too-atypical customer service interaction I had last week with a human who was significantly worse than a mediocre AI. I scheduled an appointment for an MRI. The MRI is for a jaw problem which makes it painful to talk. I was hoping that the scheduling would be easy, so I wouldn't have to spend a lot of time talking on the phone. But, as is often the case when dealing with bureaucracy, it wasn't easy.

Here are the steps it took.

- Have jaw pain.

- See dentist. Get referral for MRI when dentist determines that it's likely to be a joint problem.

- Dentist gets referral form from UW Health, faxes it to them according to the instructions on the form, and emails me a copy of the referral.

- Call UW Health.

- UW Health tries to schedule me for an MRI of my pituitary.

- Ask them to make sure there isn't an error.

- UW Health looks again and realizes that's a referral for something else. They can't find anything for me.

- Ask UW Health to call dentist to work it out. UW Health claims they cannot make phone calls.

- Talk to dentist again. Ask dentist to fax form again.

- Call UW Health again. Ask them to check again.

- UW Health says form is illegally filled out.

- Ask them to call dentist to work it out, again.

- UW Health says that's impossible.

- Ask why.

- UW Health says, “for legal reasons”.

- Realize that's probably a vague and unfounded fear of HIPAA regulations. Try asking again nicely for them to call my dentist, using different phrasing.

- UW Health agrees to call dentist. Hangs up.

- Look at referral, realize that it's actually impossible for someone outside of UW Health (like my dentist) to fill out the form legally given the instructions on the form.

- Talk to dentist again.

- Dentist agrees form is impossible, talks to UW Health to figure things out.

- Call UW Health to see if they got the form.

- UW Health acknowledges receipt of valid referral.

- Ask to schedule earliest possible appointment.

- UW Health isn't sure they can accept referrals from dentists. Goes to check.

- UW Health determines it is possible to accept a referral from a dentist.

- UW Health suggests a time on 2/17.

- I point out that I probably can't make it because of a conflicting appointment, also with UW Health, which I know about because I can see it on my profile with I log into the UW Health online system.

- UW Health suggests a time on 2/18.

- I point out another conflict that is in the UW Health system.

- UW Health starts looking for times on later dates.

- I ask if there are any other times available on 2/17.

- UW Health notices that there are other times available on 2/17 and schedules me later on 2/17.

I present this not because it's a bad case, but because it's a representative one. In this case, my dentist's office was happy to do whatever was necessary to resolve things, but UW Health refused to talk to them without repeated suggestions that talking to my dentist would be the easiest way to resolve things. Even then, I'm not sure it helped much. This isn't even all that bad, since I was able to convince the intransigent party to cooperate. The bad cases are when both parties refuse to talk to each other and both claim that the situation can only be resolved when the other party contacts them, resulting in a deadlock. The good cases are when both parties are willing to talk to each other and work out whatever problems are necessary. Having a non-AI phone tree or web app that exposes simple scheduling would be far superior to the human customer service experience here. An AI chatbot that's a light wrapper around the API a web app would use would be worse than being able to use a normal website, but still better than human customer service. An AI chatbot that's more than a just a light wrapper would blow away the humans who do this job for UW Health.

The case against using computers instead of humans is that computers are bad at handling error conditions, can't adapt to unusual situations, and behave according to mechanical rules, which can often generate ridiculous outcomes, but that's precisely the situation we're in right now with humans. It already feels like dealing with a computer program. Not a modern computer program, but a compiler from the 80s that tells you that there's at least one error, with no other diagnostic information.

UW Health sent a form with impossible instructions to my dentist. That's not great, but it's understandable; mistakes happen. However, when they got the form back and it wasn't correctly filled out, instead of contacting my dentist they just threw it away. Just like an 80s compiler. Error! The second time around, they told me that the form was incorrectly filled out. Error! There was a human on the other end who could have noted that the form was impossible to fill out. But like an 80s compiler, they stopped at the first error and gave it no further thought. This eventually got resolved, but the error messages I got along the way were much worse than I'd expect from a modern program. Clang (and even gcc) give me much better error messages than I got here.

Of course, as we saw with healthcare.gov, outsourcing interaction to computers doesn't guarantee good results. There are some claims that market solutions will automatically fix any problem, but those claims don't always work out.

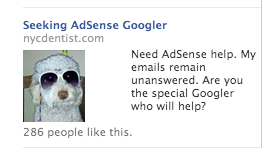

That's an ad someone was running for a few months on Facebook in order to try to find a human at Google to help them because every conventional technique they had at their disposal failed. Google has perhaps the most advanced ML in the world, they're as market driven as any other public company, and they've mostly tried to automate away service jobs like first-level support because support doesn't scale. As a result, the most reliable methods of getting support at Google are

- Be famous enough that a blog post or tweet will get enough attention to garner a response.

- Work at Google or know someone who works at Google and is willing to not only file an internal bug, but to drive it to make sure it gets handled.

If you don't have direct access to one of these methods, running an ad is actually a pretty reasonable solution. (1) and (2) don't always work, but they're more effective than not being famous and hoping a blog post will hit HN, or being a paying customer. The point here isn't to rag on Google, it's just that automated customer service solutions aren't infallible, even when you've got an AI that can beat the strongest go player in the world and multiple buildings full of people applying that same technology to practical problems.

While replacing humans with computers doesn't always create a great experience, good computer based systems for things like scheduling and referrals can already be much better than the average human at a bureaucratic institution. With the right setup, a computer-based system can be better at escalating thorny problems to someone who's capable of solving them than a human-based system. And computers will only get better at this. There will be bugs. And there will be bad systems. But there are already bugs in human systems. And there are already bad human systems.

I'm not sure if, in my lifetime, technology will advance to the point where computers can be as good as helpful humans in a well designed system. But we're already at the point where computers can be as helpful as apathetic humans in a poorly designed system, which describes a significant fraction of service jobs.

2023 update

When ChatGPT was released in 2022, the debate described above in 2015 happened again, with the same arguments on both sides. People are once again saying that AI (this time, ChatGPT and LLMs) can't replace humans because a great human is better than ChatGPT. They'll often pick a couple examples of ChatGPT saying something extremely silly, "hallucinating", but if you ask a human to explain something, even a world-class expert, they often hallucinate a totally fake explanation as well

Many people on the pessimist side argued that it would be decades before LLMs can replace humans for the exact reasons we noted were false in 2015. Everyone made this argument after multiple industries had massive cuts in the number of humans they need to employ due to pre-LLM "AI" automation and many of these people even made this argument after companies had already laid people off and replaced people with LLMs. I commented on this at the time, using the same reasoning I used in this 2015 post before realizing that I'd already written down this line of reasoning in 2015. But, cut me some slack; I'm just a human, not a computer, so I have a fallible memory.

Now that it's been a year ChatGPT was released, the AI pessimists who argued that LLMs would displace human jobs for a very long time have been proven even more wrong by layoff after layoff where customer service orgs were cut to the bone and mostly replaced by AI, AI customer service seems quite poor, just like human customer service. But human customer service isn't improving, while AI customer service is. For example, here are some recent customer service interactions I had as a result of bringing my car in to get the oil changed, rotate the tires, and do a third thing (long story).

- I call my local tire shop and oil change place and ask if they can do the three things I want with my car

- They say yes

- I ask if I can just drop by or if I need to make an appointment

- They say yes, I can just drop by to get the world done

- I ask if I can talk to the service manager directly to get some more info

- After being transferred to the service manager, I describe what I want again and ask when I can come in

- They say that will take a lot of time and I'll need to make an appointment. They can get me in next week. If I listened to the first guy, I would've had a completely pointless one-hour round trip drive since they couldn't, in fact, do the work I wanted as a drop-in

- A week later, I bring the car in and talk to someone at the desk, who asks me what I need done

- I describe what I need and notice that he only writes down about 1/3 of what I said, so I follow up and

- ask what oil they're going to use

- The guy says "we'll use the right oil"

- I tell him that I want 0W-20 synthetic because my car has a service bulletin indicating that this is recommended, which is different from the label on the car, so could they please note this.

- The guy repeats "we'll use the right oil".

- (12) again, with slightly different phrasing

- (13) again, with slightly different phrasing

- (12) again, with slightly different phrasing

- The guy says, "it's all in the computer, the computer has the right oil".

- I ask him what oil the computer says to use

- Annoyed, the guy walks over to the computer and pull up my car, telling me that my car should use 5W-30

- I tell him that's not right for my vehicle due to the service bulletin and I want 0W-20 synthetic

- The guy, looking shocked, says "Oh", and then looks at the computer and says "oh, it says we can also use 0W-20"

- The guy writes down 0W-20 on the sheet for my car

- I leave, expecting that the third thing I asked for won't be done or won't completely be done since it wasn't really written down

- The next day, I pick up my car and they fully didn't do the third thing.

Overall, how does an LLM compare? It's probably significantly better than this dude, who acted like an archetypical stoner who doesn't want to be there and doesn't want to do anything, and the LLM will be cheaper as well. However, the LLM will be worse than a web interface that lets me book the exact work I want and write a note to the tech who's doing the work. For better or for worse, I don't think my local tire / oil change place is going to give me a nice web interface that lets me book the exact work I want any time soon, so this guy is going to be replaced by an LLM and not a simple web app.

Elsewhere

Thanks to Leah Hanson and Josiah Irwin for comments/corrections/discussion.